Under a variable ratio of reinforcement (Cornish, 1978), and, even today, the slot machine is typically provided as an example of a VR schedule to undergraduate psychology students (e.g., Weiten, 2007). It has since been documented that gaming. We almost always play Q Hits, the three-reel, old-fashioned type. Three Q Hits on the center line used to pay out $5,000. Now most pay out $10,000. Over the years my wife has been quite lucky. I haven't been as lucky, but have no complaints. I keep a reasonable record of all our winnings and money spent.

In the 1930s, an American researcher named B.F. Skinner conducted a series of studies on lab rats and domestic pigeons, placed in boxes that came to be called ‘Skinner boxes’. He was trying to see if he could get them to behave in a certain way, by rewarding certain behaviour or punishing it. I won’t go into all the details. (You can read a simple explanation here.) Essentially, the rats or pigeons pressed a lever, and were sometimes rewarded with food. It could be a fixed interval (say after every five minutes, regardless of the lever) or a variable interval, or after a fixed or variable number of lever presses.

Some of the best results he got were with what he called variable ratio reward schedules. He found that, once a behaviour was established by rewarding it the first few times, he only needed to reward it intermittently. For example, a pigeon would get the reward after an average of ten presses: sometimes it would be three, sometimes ten, sometimes fifteen – the cycle of tension and release meant the pigeons would keep pressing long after he even stopped rewarding them.

A way of making money off of this had already existed for forty years.

The first real slot machine was created sometime towards the end of the 19th century. It was simple – three mechanical reels had five symbols each, and if you got three of the same symbol in a row, you won some amount. That obviously meant a casino couldn’t afford to provide a large jackpot, because even with 10 symbols, your odds of winning were 1 in 1000. As a result, the first slot machines provided ‘jackpots’ as big as 50 cents.

In the 1960s, with the help of electronics, the makers were able to assign weights to each symbol, and therefore to dictate the odds. A little while later, the first fully electronic slot machine made its debut; now, the slot machine is basically a Random Number Generator that you stop when you press a button, which maps symbols to real-looking reels based on a closely-guarded technology called Virtual Reel Mapping. This has let the casinos offer much larger jackpots with much slimmer odds.

In many ways, the slot machine is the physical embodiment of a variable ratio reward schedule, so much so that Skinner himself likened his box to a slot machine. With advances in technology, though, has come a much more thorough understanding of how to earn more money from slot machines. For the first half of the twentieth century, slot machines were relegated to the side of the floor for the wives of the ‘actual’ players. Today, they earn about 70% of the total revenue of an average casino.

Part of the reason for that is the mastery of reward schedules achieved by the manufacturers. Pay out too often, and the tension is not built. Pay out too less, and the player gets frustrated and leaves. Traditional slot machines used to pay out on about 3 per cent of all spins. Modern slot machines pay out on around 45 per cent. What the machine has done, in essence, is lengthen the time it takes to take your money. There are fewer large spikes in play, like a big win, and more little payouts over time: the most important metric for a manufacturer is more ‘Time on Device‘, because that leads to more and more revenue. Success for a casino is when a player ‘plays to extinction’, which means all of the player’s money is spent on the game.

Every aspect of the slot machine is carefully engineered to provide ‘the experience players want’. That includes dedicated sound engineers to work on music to keep the player engrossed longer, it includes the perfect ergonomics, the lights on the machine, the small vibratory feedback the machine provides on touch, all to get the player in the perfect cocoon for as long as possible. And then we get into the game itself. The casino has a neat bag of tricks: several times, even if the amount you won is less than the amount you bet, the machine will light up like you just won a jackpot. If you think the players will obviously see through this, think again. Losses Disguised as Wins (LDWs) regularly make players inflate their perception of how much they won. In addition, reels are deliberately engineered in such a way that if you need a 7 on the third reel, it will be just above the main line, looking like you just almost won the jackpot. The machine will accentuate this by slowly rolling the third reel to a stop on the wrong symbol. Even though your odds are virtually non-existent (and still the same), the near-miss is likely to make you play again. Here is a review paper of 51 studies from 1991 to 2015 documenting these effects.

Slot machines are some of the most addictive games on the planet. Machine gamblers have been shown to be addicted about three to four times faster than other gamblers. People have been seen to play right on as someone has a heart attack right next to them, collapses by the feet of their chair, as the emergency response teams arrive, the victim is treated, gets up on his feet, and leaves. Right fucking on. Players have been reported to play right through water levels rising at their feet, or through smoke and fire alarms. In fact, addicts talk about not playing to win at all. They start playing just to get ‘in the zone’, because for that time the machine has the capability to keep them completely spellbound, to stave off boredom and tedium and pain as long as they can press the lever. They speak of coming to their senses only after spending hours on the machine, having wet themselves and lost all their money, blinking with the morning sun in their eyes and wondering what the fuck just happened. After a while, you know you’re going to lose money. The problem is, you don’t care. Sometimes the rat gets no food pellets. Sometimes it gets two. Sometimes thirty. The rat never knows when it’s going to get a pellet, so it keeps pressing, over and over, becoming obsessed with it.

They’re just Skinner boxes. The rats don’t stand a chance.

Capturing people’s attention has always been the biggest challenge for any business – that is literally why the advertising industry exists, to get people to pay attention to this cool new thing which is totally going to change the world. And yet, with the explosion of the technology that brings information to you (and therefore the competition to get you to see my information), has come the arms race for attention, fierce enough that the chief product of some of the biggest companies of our time is simply users’ attention. One of Facebook’s most important metrics for measuring itself, for example, is ‘Time on Site‘. Because Facebook is selling eyeballs, it only gets to profit if you spend more and more time on it. In 2016, the average user spent 50 minutes a day on Facebook, up from 40 minutes in 2014. And that’s just the average, which means half of its 1.65 billion users spent more than 50 minutes a day on Facebook.

Ever since Facebook and Instagram implemented infinite scrolling, I’ve found myself stuck on them at times – scrolling and scrolling endlessly and fruitlessly for a long time, searching for nothing in particular, smiling at a random self-referencing meme and liking something here and there, and finding new things I should now be outraged about. Similarly with the Quora app, even – I’ve found myself scrolling frustratingly for hours, so much so that I no longer have the apps on my phone to tempt me to scroll away my time.

In the quest to capture as much user attention as possible, these apps seem to have stumbled on a similar design philosophy. The users keep scrolling. Often, they scroll past things that are not interesting. Occasionally, they will see a picture they like which gives them a dopamine hit. Sometimes, they will see an interesting article that (mostly) reinforces their worldview. They do not know when they will find those, though – they only appear randomly in their feed. So the users keep scrolling, looking for the next interesting thing.

Tinder has been downloaded more than a 100 million times, only on the Google Play Store. Its interface is invitingly simple. You see a person’s picture. You swipe left or right, based on whether you like them or not. Your next swipe could be nothing. Or it could be an interesting person you hit it off with. Or it could be the person you end up together with. Or it could be nothing. The only way to know is to keep swiping. Tinder will, graciously, offer you more swipes (at a modest price).

The Indian Government launched its own UPI app to promote digital transactions, BHIM, in January 2017. By August, about 17 million UPI transactions had been performed. BHIM’s share of that was 40%. In September, Google launched its own UPI app called Tez. By December, UPI transactions were at 145 million. BHIM’s share was down to 6%. Tez, in four months, had 52% of all UPI transactions.

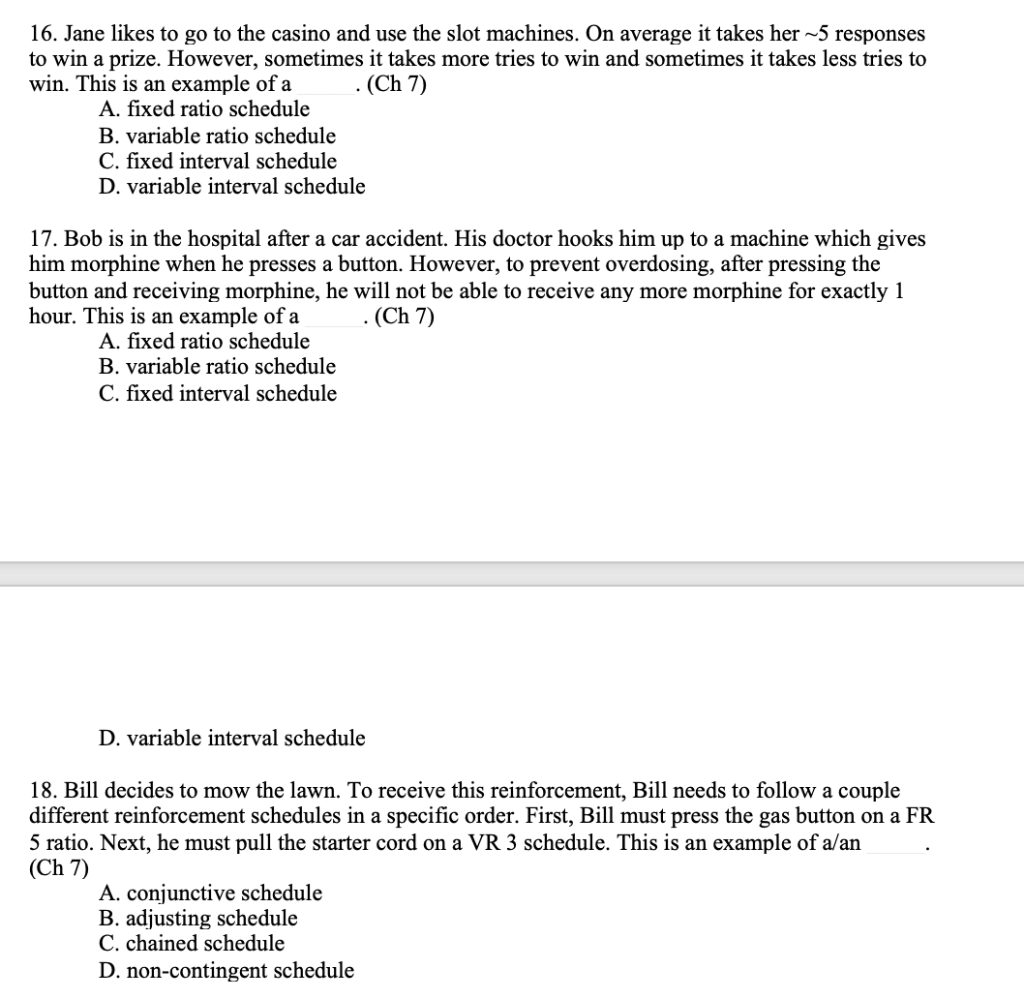

If you make a transaction above a certain amount on Tez, you get a scratch card. Most of the scratch cards will give you nothing. Occasionally, one will give you Rs. 24. Once in a while, someone will win Rs. 900, just for making a transaction. Most of the time, it will be nothing. But you don’t know which scratch card is going to give you 900, so you have to make your transactions on Tez anyway.

Do we stand a chance?

Notes

- If you’re interested in the way Slot machines work and cause addiction, Addiction by Design – machine gambling in Las Vegas is a well-written book by a researcher who knows her shit.

- Gaming also makes extensive use of combinations of reward schedules to keep players hooked. I didn’t have space to go into it, but here‘s a long-ass article talking about that in depth.

- I don’t know if this inspired the Infinite Scroll, but a 2005 study found that people unknowingly eating from bottomless bowls ate way more soup than the control.

- The Tez statistics can be found in this article.

- The abundance of articles on a simple Google search that tell you just how to use variable ratio reward schedules to hook your users by ‘driving them crazy’ creeps me out.

- One of the links in last week’s post was a music video. Nobody noticed.

- This is my 10th published blog post, having started a blog with long-winding posts in an age where blogs are dying and people are reading less and less. (I’ve always been this wise.) The fact that you read and feel strongly enough to react means a lot to me. Thank you for reading.

Regulating opponents’ behavior

What follows is a special preview from Jeff’s book, Advanced Pot-Limit Omaha Volume II: LAG Play

Once you get to a certain point in your development as a poker player — you’ve learned hand valuations and acquired the necessary technical skills to play the game — the next big step to opening up your game is figuring out how to regulate your opponents’ behavior in such a way as to make them easier to play against. That is, the next step is founded in large part on psychology.

Enter variable-ratio reinforcement.

Variable-ratio reinforcement is generally defined as delivering reinforcement after a target behavior is exhibited a random number of times. Let’s take a slot machine, for example. A gambler sits down at a slot machine and bets $1 a pull. As you would expect, most of the time the gambler will bet $1 and lose, which of course is great for the casino. But if all the gambler does is bet $1 and lose every time, eventually he will quit or go broke, and never want to play again. So, every few spins, the slot machine will reward the gambler with a payoff: $1 here, $1 there; $5 here, $1 there.

Then, every once in a long while, the machine will reward the gambler with a big payoff in the form of a jackpot.

Now, none of this quite adds up, which is how the house wins in the long run. But the promise of the big payoff, along with the intermittent rewards, is generally enough for the casino to reinforce the target behavior, which is to have the gambler keep betting $1 a pull.

That brings us to our next topic, which is the reinforcement schedule.

Slot Machines Pay Out On A Variableratio Interval Calculator

Reinforcement Schedules:

Variable vs. Fixed

There are two basic types of reinforcement schedules: variable-ratio reinforcement schedules, and fixed-ratio reinforcement schedules.

Let’s start with the latter, which is the most basic. A fixed-ratio reinforcement schedule is one in which reinforcement is delivered at fixed intervals. Let’s say, for example, that you are casino management, and you want the slot machine to pay out 20 percent of the time, or every fifth spin. So, the gambler will lose $1 four times in a row and get a payout on the fifth one every time.

The reinforcement schedule would look something like this:

Slot Machine: Fixed-Ratio Reinforcement Schedule

Lose Lose Lose Lose Win

Lose Lose Lose Lose Win

Lose Lose Lose Lose Win

Lose Lose Lose Lose Win

Lose Lose Lose Lose Win

Adjusted for payouts, the schedule might look more like this:

Slot Machine: Fixed-Ratio Reinforcement Schedule With Payouts

-$1 -$1 -$1 -$1 +$2

-$1 -$1 -$1 -$1 +$10

-$1 -$1 -$1 -$1 +$1

-$1 -$1 -$1 -$1 +$4

-$1 -$1 -$1 -$1 +$1

In this scenario, for every 25 spins, the gambler would win $18 on the five winning spins and lose $20 on the rest, for a net loss of $2. For the house, this represents a payout of 92 percent and a house edge of 8 percent.

Now, all of this sounds great, but there is a major problem: Nobody would ever play a game with a payout (reinforcement) schedule like this one!

OK, maybe “nobody” and “ever” might be a little strong, but the point remains, because it wouldn’t take long for the gambler to figure out that this slot machine pays out every fifth spin, and only every fifth spin. As a result, he would quit playing.

Using a variable-ratio reinforcement schedule is the fix for this problem.

Variable-Ratio Reinforcement Schedule

A variable-ratio reinforcement schedule uses a predetermined ratio while delivering the reinforcement randomly. Going back to the slot machine, let’s say that you once again are casino management and want the slot machine to pay out 20 percent of the time, or every fifth time on average.

Now, your reinforcement schedule may look something like this:

Slot Machine: Variable-Ratio Reinforcement Schedule

Lose Lose Lose Lose Win

Lose Win Lose Lose Lose

Lose Lose Win Lose Lose

Win Lose Lose Lose Lose

Lose Lose Lose Win Lose

And adjusted for payouts, the schedule would look like this:

Slot Machine: Variable-Ratio Reinforcement Schedule With Payouts

-$1 -$1 -$1 -$1 +$2

-$1 +$10 -$1 -$1 -$1

-$1 -$1 +$1 -$1 -$1

+$4 -$1 -$1 -$1 -$1

-$1 -$1 -$1 +$1 -$1

In aggregate, the expectation is the same: Over 25 spins, the gambler will still realize a net $2 loss, for a 92 percent payout and 8 percent house advantage for the casino. But in reality, this scenario is far more likely to achieve the desired result, which is to have the gambler keep playing. In contrast to the fixed-ratio reinforcement schedule, a variable-ratio reinforcement schedule with a 20 percent reinforcement ratio provides clusters of payouts (for example, back-to-back wins), as opposed to having spins (or blocks of spins) on which the gambler can say for certain that he will lose, and quit playing as a result.

This is because the variable-ratio reinforcement schedule does not specify when the payouts occur, but only how often they occur on average.

That said, in regard to pot-limit Omaha, there is one major application for variable-ratio reinforcement that I will discuss another time. That application is the continuation-bet (c-bet).

2 4 | |

Comments are closed.